Words Matter

Globalized language and geopolitics in the work of Dagoberto Rodríguez

Diana Cuéllar Ledesma

A perversely beautiful event took place in May 2016. After the capture of Palmyra by Syrian troops, the Russian government of Vladimir Putin organized a symphonic concert in the ruins of the city´s Roman amphitheater. Almost a year had passed since the Islamic state filmed on that same stage, considered a world heritage of humanity by Unesco, a video that recorded a sort of staged performance (the authenticity of the recording could never be verified) in which a group of minors killed twenty-five Syrian soldiers in front of a crowd of spectators sitting in the stalls.

Under the motto “Prayer for Palmira. Music revives old walls”, the concert of the symphonic orchestra of the Mariinsky theatre of St Petersburg in Palmira was clearly a strategic move by Russia to improve its image in the media after its intervention in the Syrian war. Nevertheless, and regardless of geopolitical considerations, the aesthetic portent of the event gave rise to an unusual image of poetry in the midst of war. However, that concert was a preconceived and cautiously orchestrated event. In contrast, many other events of enormous aesthetic dimensions take place in the daily life of the most heartbreaking contexts and in spontaneous ways. The exhibition Tus manos están bien (Your hands are fine) is inspired by one of these moments.

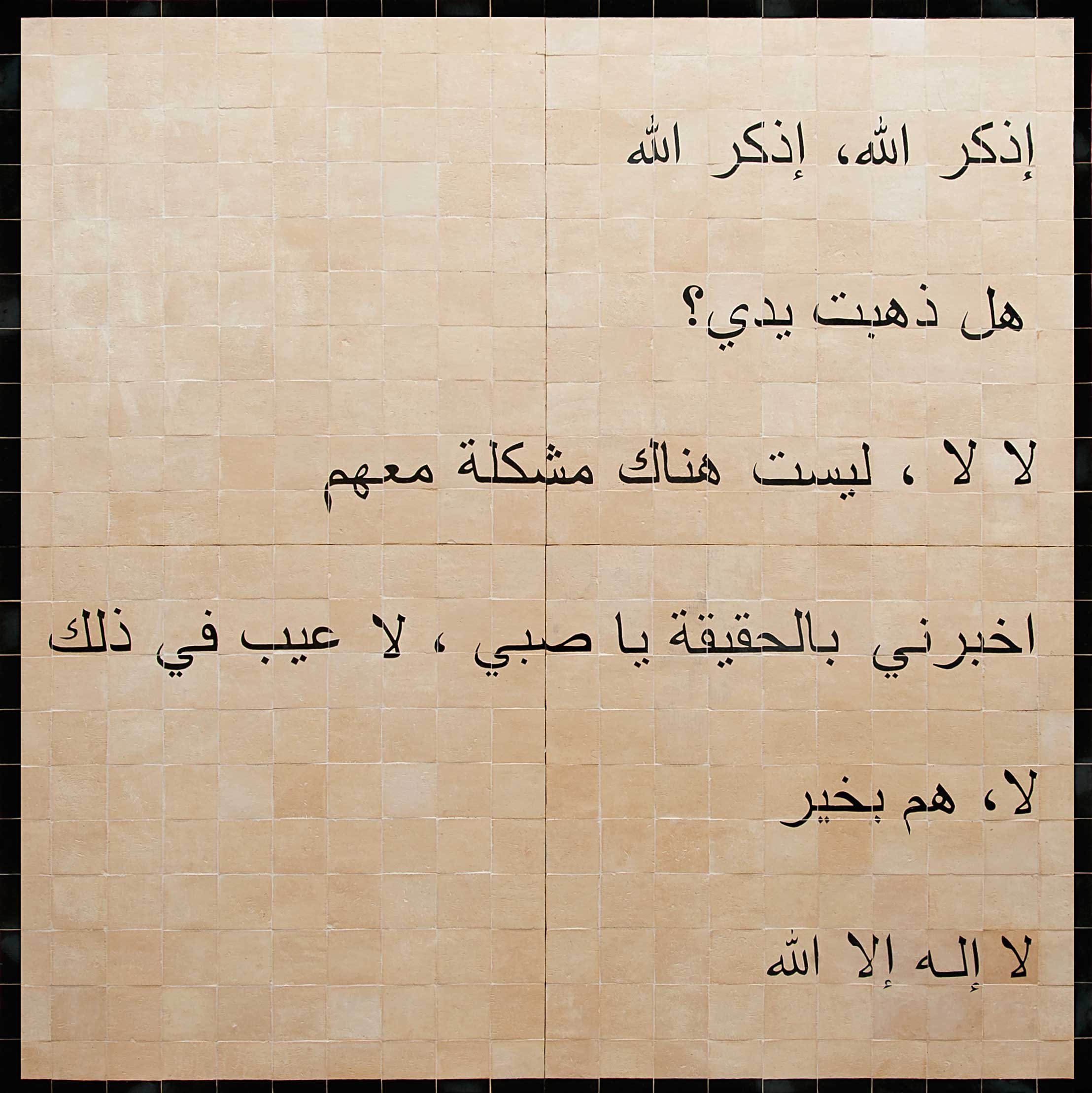

Dagoberto Rodríguez has successfully (de)coded a situation of almost mystical beauty that was recorded in a short video of rudimentary quality made by a combatant of the Syrian war and spread through the social network Twitter. After losing both his hands after firing an anti-tank missile on the outskirts of Damascus, an old man was comforted by his young battle partner. Against all evidence, he assured the injured soldier that his hands were fine and immediately invited him to praise God. The injured man agreed and said his prayer. It is an act of overwhelming and extreme faith. The dialogue, whose Psalmical structure resembles a Quranic verse, has been captured by Rodríguez in a mosaic mural made by hand using the ancient technique of Arabic tiling. Due to the opacity of the sign, which makes the Arabic characters unintelligible to the majority of the public in the West, the content of the conversation is hidden behind the beauty of calligraphy and its exquisite stone quality. The title of the piece, Tweet, synthesizes the contradictions between a hyperconnected world and the survival of premodern religious practices. On the other hand, the fact that the Syrian war is occurring in real time and by means of similar publications made by those same combatants and victims, has resulted in the reconfiguration of the role that conventional media has historically had in shaping the collective imagination and stories of armed conflicts. It involves, as it were, the rise of polyphonic stories that emerged from below, which complement, or even replace, the great narratives articulated by powerful television companies or the written press. In this way, this piece encompasses and exploits many of the multiple complexities that such a brief war scene may contain, such as that randomly found by the artist in the vastness of cyberspace.

Although formally Tweet seems to move away from Rodríguez´s previous work (which among other things has explored the intersections between design and art, and developed a very personal universe of watercolor images), his underlying concern powerfully and innovatively connects the piece with the previous trajectory of the artist. It is a work about faith, war, telecommunications and contemporary geopolitics, but, also, and above all, it is an inquiry into the power of the word. It is revealing that the aspect of the aforementioned video that has most attracted the attention of the artist was not the image itself, but, precisely, the dialogue, the beauty of the Arab characters and the fact that an oral exchange in a context of pain and urgency could be structured as poetry. This is not surprising if we consider that in Islam, language has a huge and comprehensive reach. It is one of the three religions commonly referred to as “from the book,” that is to say, they come from the belief that “the word” of God is contained in one or more texts that serve as the rules and spiritual guidance of its believers. It also has the peculiarity that its sacred book condenses two dimensions of language: writing and orality. Indeed, the word Quran is usually translated as “recitation” to underline the fact that the word of Allah is not limited to the written text, but must also be transmitted orally, through singing and recitation.

Rodríguez has demonstrated his intention to pay tribute to the man who lost his hands through this piece, whose refined quality is completely manual and requires enormous dedication and skill on the part of the craftsman. The image of “leaving your hands” modernizes the old counterpoint between weapons and words or, equally, war and art, two opposing forces that have remained alive in practically every culture on the planet throughout history. On a symbolic level, hands have great relevance in Arab culture: their use is regulated by sacred law and they are, together with the eyes, the most important aesthetic expression of the body. The hand is also the human tool par excellence. This has special value for an artist like Dagoberto Rodríguez, whose initial work within Los Carpinteros collective was focused on manual work with wood and other materials that are usually associated with crafts and not with fine art. Therefore, this return to the manual is a condemnation of that outdated hierarchy of creativity and a dialectical return within Rodríguez´s career. In general, and as we will see further on, the works that make up the exhibition are based on situations of complexity and contradiction (industrial and artisanal, technology and nature, high and low culture, art and war) that the artist synthesizes, resolves or comments on through humor and poetry.

It is important to highlight that the video that inspired the work was circulated on a social network, Twitter, whose concept and dynamic evoke the same mechanisms as oral communication (immediacy, replication and rapid circulation and gossip). By bringing the aforementioned dialogue to stone through an ancient artisan technique, a subtle contrast is established between the speed and volatility of the information disseminated through digital platforms and the old practice of capturing the texts in stone to make them last. Not least, in English the word twitter refers to the song of a bird, that is, it alludes to a natural order. However, at present and globally, this word is usually associated almost par excellence to the homonymous social network, that is, to the field of technology. This displacement of meaning makes evident the living and changing character of language, something that the school of analytical philosophy has underlined in the past. It was precisely one of the analytical philosophers, John L. Austin who, through theorizing about “speech acts,” concluded that things can literally be done with words. This means that language itself constitutes action and reality and is not limited to capturing them.

Language is and has been an element of great importance in the history and sensibility of Cuba. It could not be any other way in a country whose national hero is a poet. From the power of words, he knew how to satiate the Cuban revolution very well. Fidel Castro did not theorize about the act of speech and probably never even heard of John Austin. The philosopher, however, could well have used the Cuban leader as a reference in his dissertations on the performative power of language. Not without reason, analysts and historians have highlighted the importance that Castro gave to the dissemination and consolidation of his personal image in the mass media. Both locally and internationally, thousands of photos and videos managed to position him as a world icon, presenting him on many occasions as a charismatic and brave leader, and the Cuban revolution as a successful historical process of harmony and social justice. However, the propaganda of the regime was not transmitted exclusively through the exploitation of the technical image. Fidel Castro´s long speeches, as well as his lapidary and provocative phrases, have become a distinctive feature of his personality. The revolutionary rhetoric and its ideological slogans spread in the media and filled the streets of the island, whether they were written on the walls, displayed on fences or through posters in offices and schools. The Castro regime also knew how to appropriate the words of historical figures giving them new meanings at their convenience. The most paradigmatic case of this is probably that of the national hero José Martí, whose vocabulary in the struggle for independence in Cuba against Spain back in the 19th century was given anti-imperialist connotations towards the United States in accordance with the interests of the Cuban bloc-soviet during the cold war.

In the series Emblemas (Emblems) (2018) Rodríguez takes up some of these revolutionary slogans and presents them with the aesthetics of the American car logos of the mid-twentieth century. Those automotive vehicles, symbols of capitalist development in the United States after World War II, were disappearing from the streets of the world with the gradual incorporation of more recent models. It is a delightful paradox that in Cuba, these cars have remained in full use throughout sixty years of communism, even becoming part of the tourist-visual repertoire of Havana, where they are known as “almendrones”. In the Emblemas series, the logos of brands such as Ford, Pontiac and Cadillac have been replaced by phrases typical of Cuban political discourse and, sometimes, of popular speech. In this regard it is fascinating that, since revolutionary vocabulary and rhetoric are such suffocating presences in the lives of Cubans, some of the phrases of the revolution have been incorporated into colloquial speech after having passed through their respective processes of appropriation and deviation of meaning, almost always with a tendency towards humor and culture of the “jodedera” (banter). Again, language works in unpredictable ways. Finally, in this series, objects that once were brand identities and ostentation of luxury become carriers of radically different messages than they originally had, but also, and this is important, they become sumptuous objects thanks to the process of the commodification of art. In this way, the artist proposes an ironic wink towards the processes of circulation and fetishization not only of art, but also of discourses and ideologies.

The accelerated circulation of content and drifts of meaning have become increasingly common situations in this globalized world. For example, In 2006, journalist Spences Ackerman reported, the great success that the song Gasolina had among Kurdish fuel traffickers during the Iraq war. The strange and fascinating appropriation of one of the most representative tracks of reggaetón musician Daddy Yankee is a reliable example of the scope of this unusually successful music genre, which has been controversial because of the sexual content of some of its lyrics and the way it is danced to. And it is against rap and hip hop, two very similar music genres which reggaetón has been influenced by, the latter distinguishes itself due to being danceable music. Its most representative step is popularly known as “perreo”, and consists of shaking the hips with vigor and cadence. Its name refers to the fact that it is usually danced as a couple in a way that the arrangement of the bodies emulates the position that dogs and other animals use to perform intercourse. Nevertheless, and by virtue of the profuse media and social universe in which it emerged, reggaetón has developed very particular lyrics that, far from being constricted to sexual content, is full of references to regional and international politics and quotes from popular, mass and even so-called “high” culture from various regions of the planet. Attentively listening to some songs has revealed to Dagoberto Rodríguez some unexpected aspects of this type of music. He has focused on them to execute his recent Reguetón series.

The artist selected certain fragments of songs to inscribe them in stone. In this series, the fact that many reggaeton lyrics show little difference to political or religious discourses when they are removed from their original context is significant. On the other hand, on many occasions, and after its bustling vitalism and overwhelming aesthetics, there are underlying existentialist aspects that accuse the human search for the transcendence and meaning of life. The fact that the roots and impact of reggaeton are located especially in Puerto Rico and among Latino communities in the United States, has led to its contents being expressed equally through very local Spanish jargon as well as Spanglish. Despite the above, the genre has remained mainly in the Spanish-speaking realm, a situation that has caused unusual cultural twists worldwide, such as the fact that the most searched word on Google in 2017 was one spoken in Spanish (“despacito/slowly”, thanks to the song known by that same name popularized by Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee) or that the biggest stars in international music are looking to sing in Spanish and incorporate the reggaetón aesthetic more frequently in their productions with the intention of increasing their sales and popularity. Therefore, both musically and lyrically, reggaetón has produced texts with a dense cultural weight and has favored dynamics that underline and repower the multidirectional crossed identifications so characteristic of our time.

Despite the above, and as a result of the dynamic of the music industry, reggaeton has been classified and typecast simplistically as Latin music, and has remained in the international consciousness as such. An in-depth analysis such as that conducted by ethnomusicologist Wayne Marshall confirms the above, yet also highlights the transnational dimension of this cultural phenomenon, which is the result of exchanges and contamination between the cultural background of the circum-Caribbean region and American urban music. In reggaetón and its extensive stylistic circles, a productive pulse has also been established between the most recent technological resources and the presence of musical instruments and rhythmic patterns of ancestral Afro-Caribbean roots. In this context it is not surprising that the genre had an enormous impact on Cuba, but the Cubans, proud of the great musical contributions that their country has made to the world, have refused to speak of Cuban reggaetón and instead the term cubatón to refer to the local production of this type of music.

For a long time, and even today, the rejection of reggaeton was almost common place among the bulk of Latin American intellectuals and in certain social sectors in Spain. This has been mainly because of two reasons: a legitimate and attentive criticism of the sexist character of its lyrics, and the widespread belief that on a musical level it was a poor genre with few contributions. Regardless of whether both issues are widely discussed, it is certain that reggaetón is a complex and rich phenomenon that merits careful analysis. This was done in 2009 by a group of specialists whose academic and theoretical reflections were collected in a monographic volume published by Duke University in the United States. Ten years later, Puerto Rico´s political events have once again brought to light this cultural phenomenon, its impact on the configuration of subjectivities and its areas of contact/political impact. Following the leak of WhatsApp conversations between the now former governor of the island, Ricardo Rosselló, and eleven men from his nearby circle, Puerto Rican society, tired of decades of bad administrations, corruption and political class cynicism, took to the streets to demand the resignation of the governor. Among all the celebrities that supported the cause, singers Bad Bunny (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) and Residente (René Juan Pérez) particularly stood out. The song Afilando los cuchillos (Sharpening the knives), written and performed by the duet, became a kind of anthem for the protests, and social networks began to blaze with memes that compared the celebrities with ideologues and social-political leaders such as Karl Marx or Ernesto “Ché” Guevara.

Over twelve consecutive days dozens of rallies in repudiation of Roselló took place in Puerto Rico. On July 24, a massive dance/protest session gathered on the steps of the Metropolitan Cathedral of San Juan. A few hours prior to the event, singer-songwriter Tommy Torres posted on Twitter asking what time the event had been organized for. The tweet in question immediately went viral due to the accurate precision with which Torres referred to the collective dance session (“What time is that combative perreo on for?” were literally the musician´s words). The term “combative perreo” was coined to refer to this type of unusual practice of political, carnal, mass and festive opposition. The same night that the combative perreo took place, Ricardo Roselló resigned from his position.

In the works gathered here Dagoberto Rodríguez works with various textures and breaches of language. The shared setting of three apparently unrelated events in time, space and concept allows the artist to explore and reflect on the scope of language as a territory for the conformation of subjectivity, the configuration of stories and the exercise of power. The exhibition also includes different historical forms of writings and texts of a diverse nature. Your hands are fine serves as a kind of exhibition-book or, to be more precise, exhibition-tablet, establishing a historical-conceptual link with contemporary digital tablets and posing a collateral observation of history and the mechanisms of its elaboration. In these works, words matter and act. Rodríguez emphasizes the processes of a living story, which is written and erased, disseminated and made viral, sung and prayed. If, as Ludwig Wittgenstein said, the limits of our language are the limits of the world, in these exercises of enlargement, dislocation and linguistic diversions worlds widen and ideas shake (or perrean).