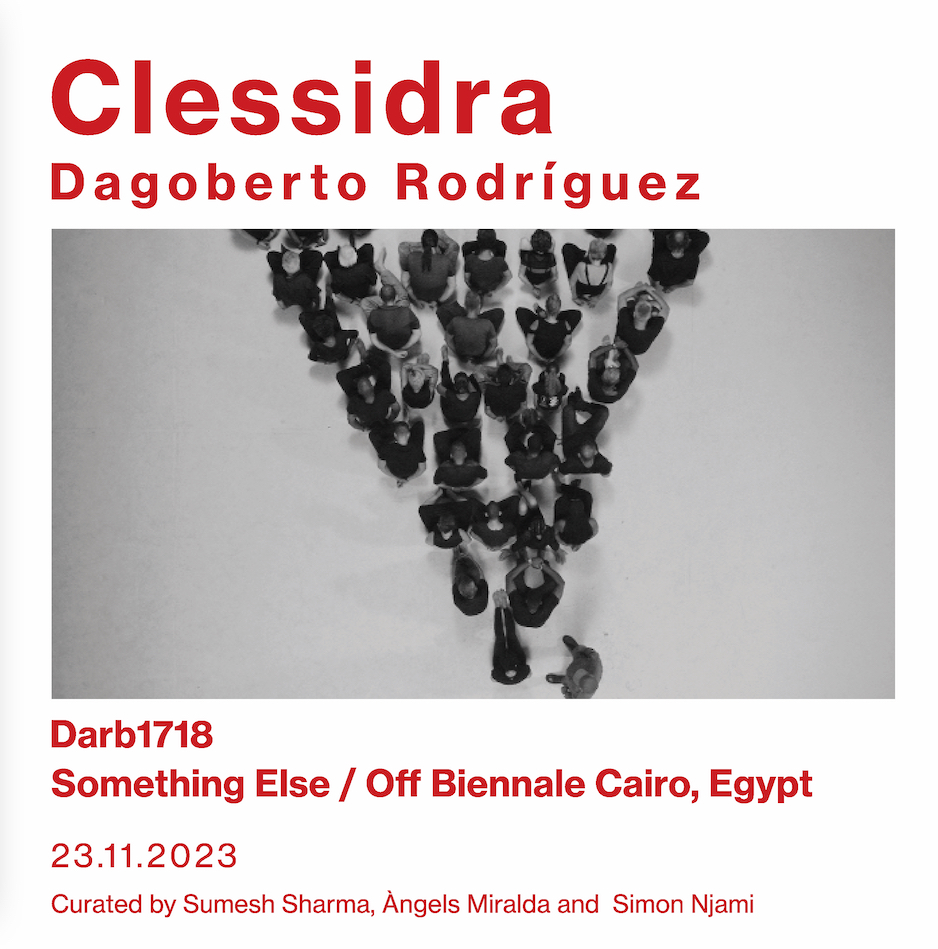

14/11/23

14/11/23

Categoría: Curator Text

14/11/23

14/11/23

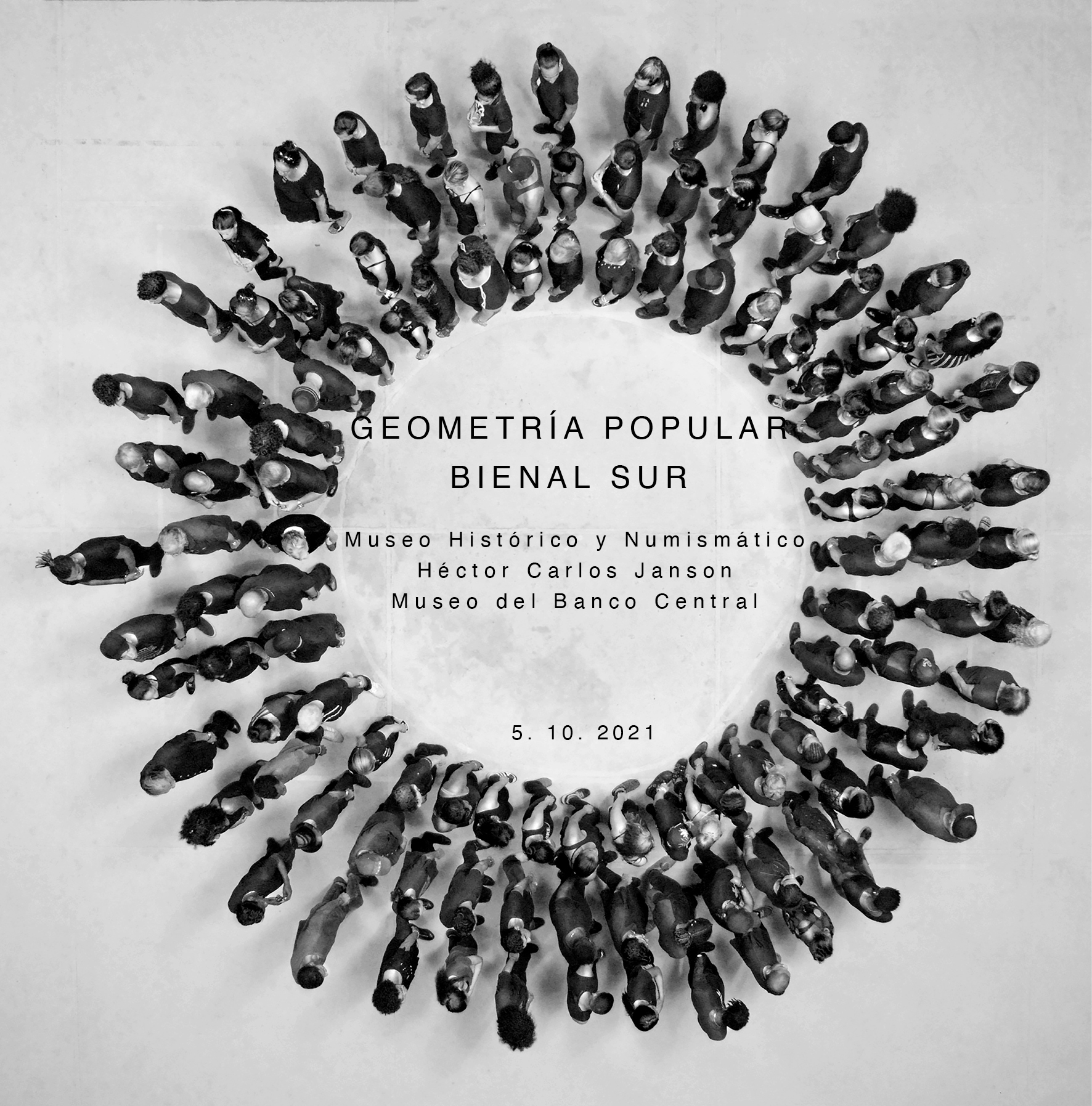

04/10/21

04/10/21

LAS FORMAS DE LA ECONOMÍA O LA ECONOMÍA DE LAS FORMAS. COMISARIADA POR FLORENCIA BATTITI. BIENAL SUR 2021, BUENOS AIRES

Curator Text 21/01/21

21/01/21

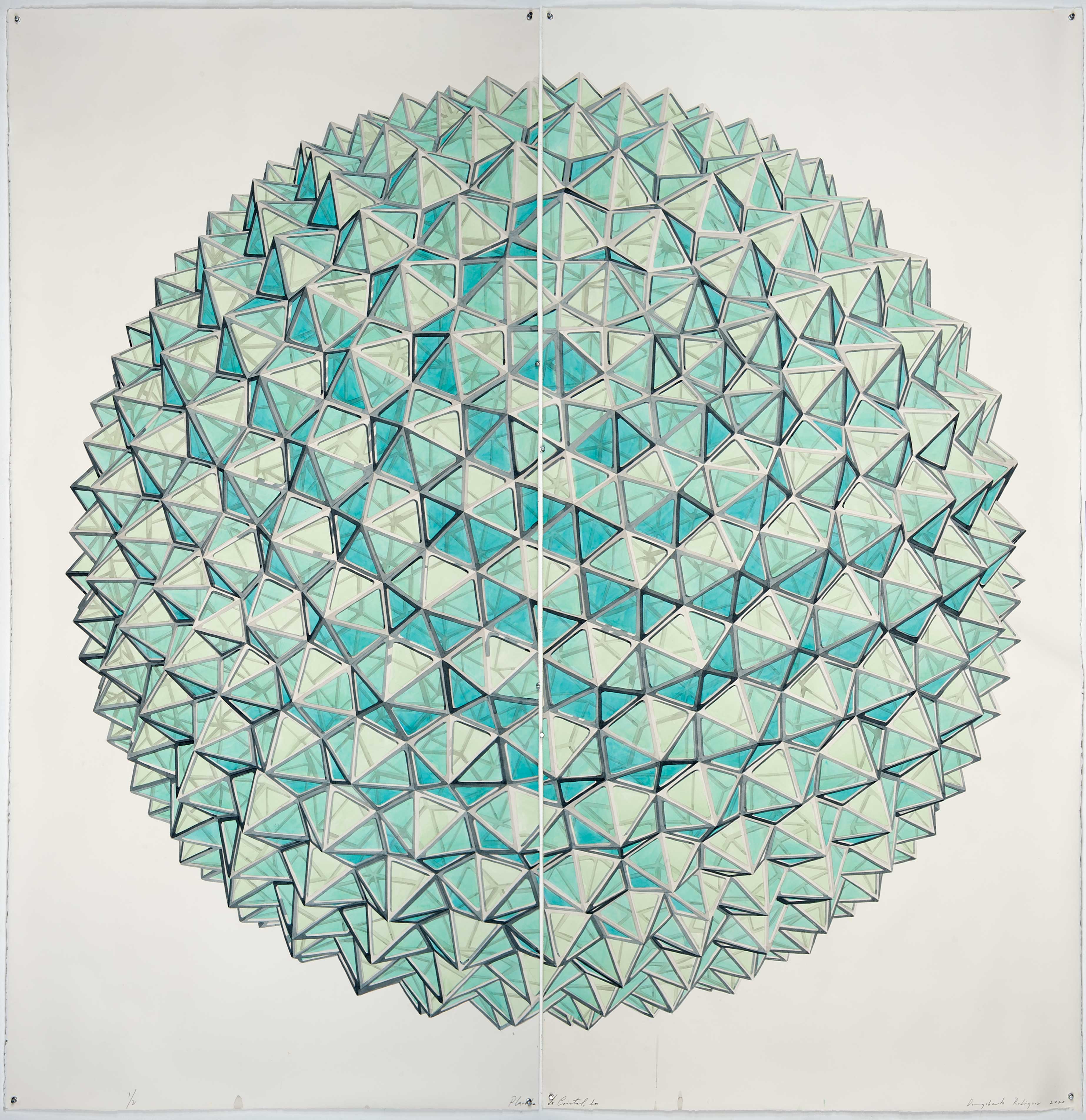

PLANETA DE CRISTAL. CURATED BY ALUNA ART FOUNDATION AT PIERO ATCHUGARRY GALLERY, MIAMI, USA. UPCOMING EXHIBITION

Curator Text 21/01/21

21/01/21

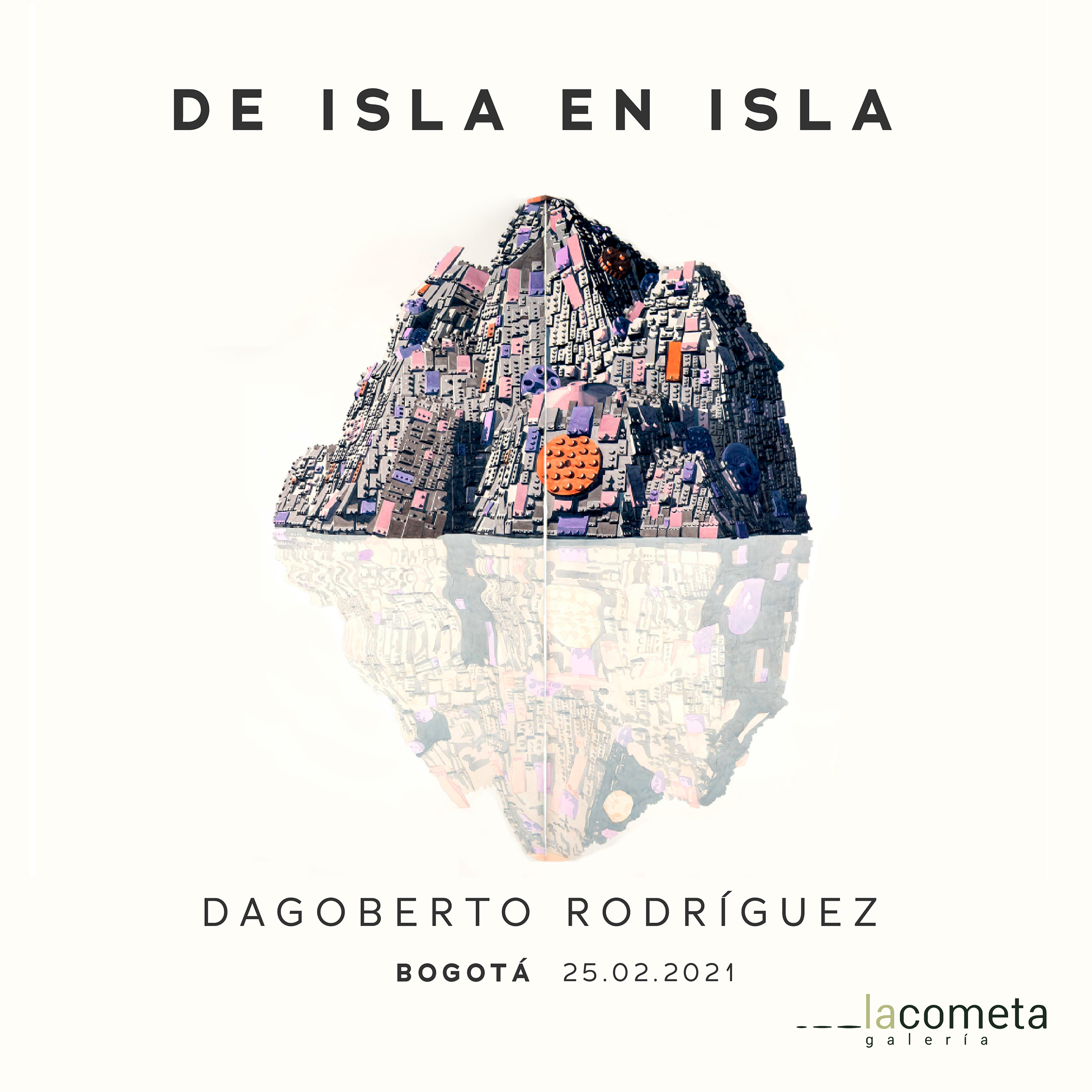

DE ISLA EN ISLA. próximamente en galería La Cometa, Bogotá. Colombia

Curator Text 22/07/20

22/07/20

ARTISHOCK. LA GUERRA NUESTRA DE CADA DÍA. ANDREA PACHECO

Curator Text 18/02/20

18/02/20

INVITACION: Cada forma en el espacio es una forma de tiempo que se escapa

Curator Text Press ReleaseCada forma en el espacio es una forma de tiempo que se escapa

A más de veinte años de la muerte de Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1951-1996) su obra parece no envejecer. Por el contrario, da la impresión de que rejuvenece, gracias a la frescura con que su legado sigue encantando a espectadores y artistas aun hoy. Su elegancia en el espacio, su capacidad de síntesis y su marcada tención poética, lo inscriben en esa genealogía de artistas que elevaron la sutileza y obviedad de algunos materiales a las simas del arte más refinado.

El autor de Untitled (Perfect lovers), fue igualmente eficaz asumiendo el tema político. Su trabajo junto al grupo Material en los años ochenta y parte de su obra en solitario así lo demuestran. Es notorio en estas obras de confrontación político-social, el activismo en torno a la denuncia de crímenes cometidos contra la comunidad gay a lo largo de la Historia, los embates e implicaciones políticas de la pandemia del SIDA en sus primeros años y las consecuencias de la circulación indiscriminada de armas de fuego en los Estados Unidos.

Pero Felix Gonzalez-Torres es solamente una de las figuras cimeras del arte pos-mínimal y pos-conceptual. Su trabajo estuvo inspirado en el de otros artistas y su legado se puede apreciar en muchos creadores que le han precedido: el proyecto expositivo Cada forma en el espacio es una forma de tiempo que se escapa, pretende abrazar esta pulsión, este modo de hacer en el arte contemporáneo más allá de la trascendencia personal de una figura cimera del arte contemporáneo. No es un homenaje en el sentido convencional de la palabra porque sería como asumir que corre el peligro de ser olvidado y creemos que su legado está más vivo que nunca (no en vano la próxima edición de la Feria de ARCO en Madrid le estará dedicada). El proyecto es una celebración, a propósito de este modo de enfrentar la creación, una oportunidad para reunir obras y artistas que de un modo u otro se encuentran cerca de esta sensibilidad.

– Solveig Font

08/01/20

08/01/20

Jerome Sans: Text for «Visión de Túnel», Sabrina Amrani Gallery Exhibition

Curator TextThrough the Tunnel

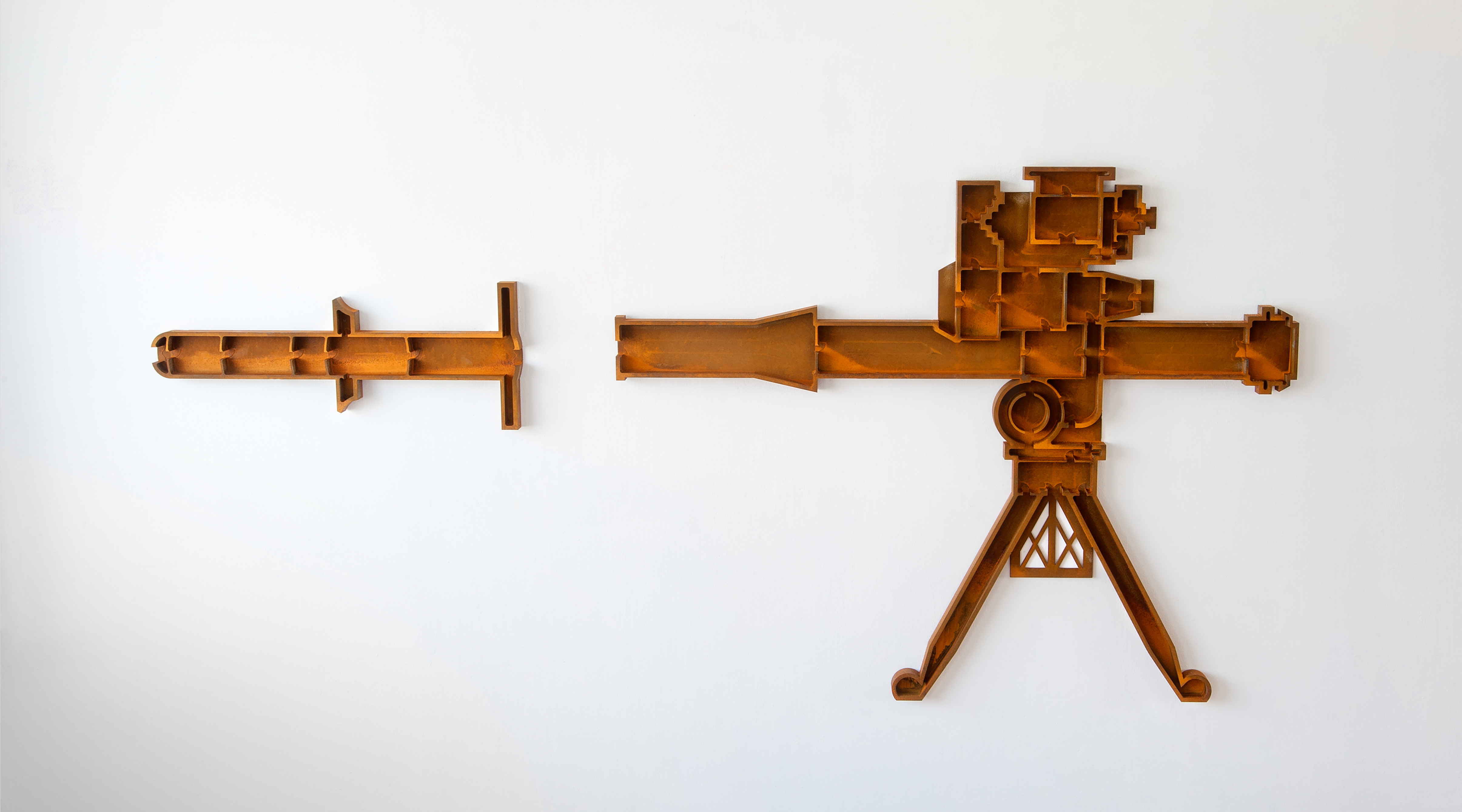

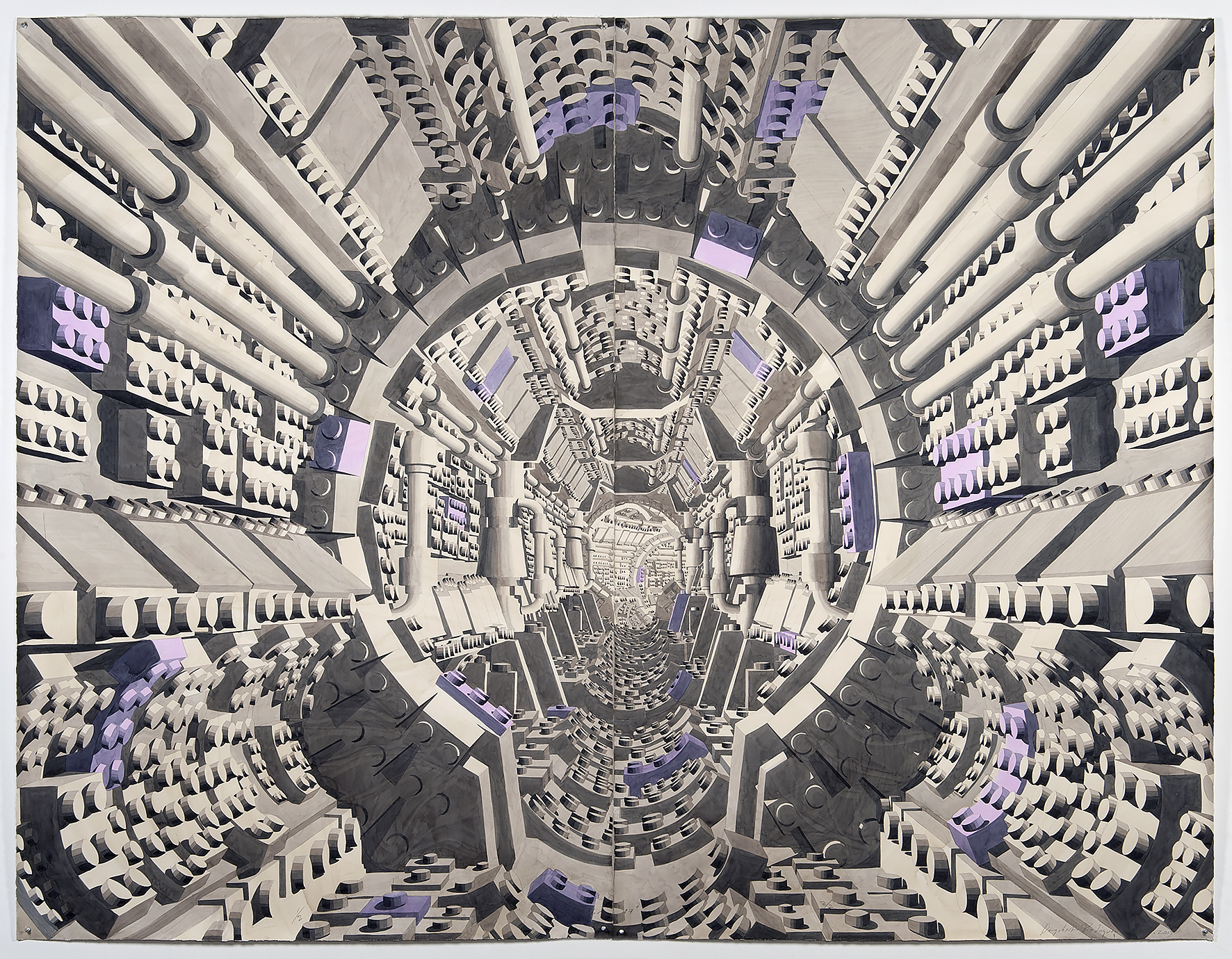

Dagoberto Rodríguez’s first solo exhibition at Sabrina Amrani Gallery, Visión de túnel focuses on a new ongoing series of watercolors depicting simple futuristic architecture of a possible future, as variations around the image of the tunnel and the corridor. From these playful visions of a mechanical world built with Lego blocks emanates paradoxically a dystopic atmosphere without the slightest trace of humanity. These tunnels transport us into a space that is not real nor located. They increase the experience of gravity and spatiality, exerting a strong force of attraction towards the depths. For the Cuban artist, living between Havana and Madrid, these drawings constitute a strong working methodology. The use of watercolor is fundamental to his creative process, as a way of working, revising and archiving his ideas, which are often based on a fantasy of possibilities for any given situation. Drawing also plays an integral part, as a technical tool for artistic elaboration, like carpentry or architectural sketches. Aircraft turbines, aerospace nacelles, aeronautical structures, urban infrastructure have for many years colonized his imagination. “For Cubans, living on such an isolated island, a plane is like a bridge taking you into another dimension, like an escape window[1],” he said about his fascination for utopia architecture and aeronautics. “However, my galaxy is right here on Earth. I want to reach a realm that’s within our terrestrial parameters and social culture[2].” Following this state of mind, Visión de túnel opens itself as a new chapter, since the end of his 27 years of collaboration with the historical Cuban collective Los Carpinteros in 2019, projecting the beginning of his solo career into a new episode.

In-between Spaces

The tunnel is in itself a polyphony of meanings, a polysemy which symbolizes all the dark, anxious, painful crossings or expectations that can lead to another life. Meticulously executed, the watercolors are of a monumental scale. This medium requires letting go while striking a balance between control and freedom of the gesture. Watercolor is the medium of choice for text illustration, from Egyptian or medieval manuscripts. Immersive, these drawings catch the eye, as if you could pass to the other side of the mirror or get sucked in. They only become even more credible thanks to tenfold illusionist effects that encourage this transition to another world. Dagoberto Rodríguez creates ultra-contemporary and urban narratives of a mechanical, cold and dehumanized world bathed into an electric light … A kind of outside world, closed in itself, enigmatic, without landmarks and of which we do not know if it is dreamlike, dystopic or concrete.

Tunnels and corridors are covered and dark communication paths with no clear location, leading us through the darkness from one area of light to another. They convey the image of the irreversible, the trial or of the passage from one state to another. At the end of each tunnel, a door symbolizes its infinite nature. The tunnel is the illusion of perspective, its emblem, according to Alberti’s definition of the painting as an open window to the world. Within the epic painting, the whole enigma of the world and the history of painting is at stake. It also alludes to today’s racing games on our smartphones or to virtual reality, to all these windows and multiple screens that suck us into information tunnels.

A World in Lego

In the heart of the corridor, we are between two indistinct spaces, as in transit, with no possibility to escape. While they may seem unlimited, these tunnels still hold us prisoners. Are those tunnels embodying the prison of our knowledge or of our certitudes? They have a false horizon. Wandering towards the light at the end of the tunnel as in Plato’s cave, we do not know if we will come across the exit or if it is only the light towards the next corridor that guides us. It appears that those tunnels generate feelings of claustrophobia, stagnation, insecurity and perhaps also frustration. They represent the emblem of the contemporary world where all our dogmas have been overthrown and where we do not know where we are going. To quote Milan Kundera in Identity: “I would imagine life before me like a tree. I used to call it the tree of possibilities. We see life that way for only a brief time. Thereafter, it comes to looking like a track laid out once and for all, a tunnel one can never get out of.[3]” Foucault had already spoken in Discipline and Punish of “conceptual dungeons of incarceration”. Those tunnels also refer to Cuba’s endless history, whose future directions cannot be predicted. The son of a keen astronomer, Rodríguez grew up in Cuba in a socialist environment, a “communist science fiction”, “a failed utopian state[4]”, to quote him. From Cuba’s limited access to technology, he inherited a kind of “Robinson Crusoe syndrome[5]”. Having to do things by himself, step by step, through recycling and inventive resourcefulness has been his way to find a new language of expressive system. Maybe that’s why all his architectural fantasies are built in Lego, a game with elementary principles and rules. Then, the Lego bricks could be disassembled, deconstructed or agglomerated to new blocks to expand at any time, like a huge construction site. This Lego world can also collapse at any moment as Cuba’s communist utopia. It is also the image of the extreme fragility of today’s world of images and information, where no construction is solid anymore.

Retrofutur and Wormholes

Dagoberto Rodríguez’s watercolors evoke simultaneously the visionary drawings of Yona Friedman’s Spatial City (1959–60) or Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon (1956–1974) as well as the sci-fi visions of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or George Lucas’s Star Wars IV Death Star (1977). In response to the unbridled urbanization of post-war Europe, some architects began designing in the late 1950s megastructures as new models of urban planning, more mobile, more relational and in line with technological progress and new lifestyles. These futurological visions aimed to free the individual from formatting, by proposing mobility and the network as paths to emancipation. Therefore, Rodríguez’s works recall the famous labyrinthine stairs of Escher from which we never know where they begin and where they end. They also remind the image of the wormhole, this shortcut through space-time, which would theoretically allow travel from one point to another, as science fiction predicted since the 1960s, being always ahead of science.

Migration Corridors

The tunnel is also a reference to all the invisible souls who worked in painful and dangerous conditions. These are spaces without air, without light, inhospitable, even inhuman. They are also sometimes death row. Thus, the railway line is also the image of the collective or social life and of the common destiny. But railway tunnels are also human prisons, where harmful and arduous human activities such as mining or tunneling occur. In this sense, the artist thinks of the drawings of the Mexican art brut artist Martín Ramírez (1895–1963). In the hope of finding a job that could feed his family, Martín Ramírez emigrated to a new El Dorado, the United States, at the age of thirty. In Northern California, he works in mining and railway construction. Subject to mental disorders, he was interned in 1931 at Stockton State Psychiatric Hospital, from where he escaped several times and returned each time of his own free will. Suffering from schizophrenia, he began drawing there in 1935 since when he became obsessed with railway tunnels. Moreover, as for the Mexican artist, the tunnels evoke the idea of an Eldorado for all migrants that risk their life by trying to take the Channel Tunnel between France and United Kingdom, even if it is dangerous. It symbolizes all the unbridled movement of populations in the hope of a better life.

Vision Tunnel

When vision is impaired while driving an aircraft, a car or when the individual crosses a road or passes near bridges, tunnels or underground tracks, the loss of peripheral vision is called “vision tunnel”. It is also a metaphor for the narrowness and the closure of an individual’s mind. Maybe tunnels metaphorize the dogma of education, of the formatting of minds, which makes history repeat itself endlessly, generation after generation, instead of opening up to other visions and perspectives. Today’s world forces people to be on a railroad to be recognized and valued. We are caught in a unique tunnel, which will probably never cross a parallel vision. In fact, for Dagoberto Rodríguez “Millions of people cohabit in large cities, but never manage to integrate completely. Even though the world has generally become a much more comfortable place than say even 20 years ago in technological terms, thanks to cellphones, the internet and so forth, we haven’t caught up socially or emotionally in terms of interaction[6].” His tunnels, empty of all human presence are visions of a dehumanized world where social interaction is becoming increasingly rare.

In Visíon de túnel, Dagoberto Rodríguez expresses himself through symbolic and philosophical narratives open to multiple interpretations: “My work is certainly metaphorical and symbolic, and metaphors often have profound conceptual value,” he wrote. “The arsenal of objects that we interact with everyday holds huge symbolic potential for my narratives. […] Architecture is also an object, capable of generating a language and expression[7].”

To be continued…

Jérôme Sans

[1] Quote from “Poetic Activism: Dagoberto Rodríguez in conversation with Jérôme Sans” in SANS J., BAITASSOVA D., Racing the Galaxy, Milano, Skira, 2019.

[2] Ibid.

[3] KUNDERA M., Identity, [translated from the French by Linda Asher], New York, Harper Flamingo, 1998, p. 75.

[4] Quote from “Poetic Activism: Dagoberto Rodríguez in conversation with Jérôme Sans”, op. cit.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

27/08/19

27/08/19

Diana Cuellar: Text for «Tus manos están bien», Ivorypress exhibition

Curator TextWords Matter

Globalized language and geopolitics in the work of Dagoberto Rodríguez

Diana Cuéllar Ledesma

A perversely beautiful event took place in May 2016. After the capture of Palmyra by Syrian troops, the Russian government of Vladimir Putin organized a symphonic concert in the ruins of the city´s Roman amphitheater. Almost a year had passed since the Islamic state filmed on that same stage, considered a world heritage of humanity by Unesco, a video that recorded a sort of staged performance (the authenticity of the recording could never be verified) in which a group of minors killed twenty-five Syrian soldiers in front of a crowd of spectators sitting in the stalls.

Under the motto “Prayer for Palmira. Music revives old walls”, the concert of the symphonic orchestra of the Mariinsky theatre of St Petersburg in Palmira was clearly a strategic move by Russia to improve its image in the media after its intervention in the Syrian war. Nevertheless, and regardless of geopolitical considerations, the aesthetic portent of the event gave rise to an unusual image of poetry in the midst of war. However, that concert was a preconceived and cautiously orchestrated event. In contrast, many other events of enormous aesthetic dimensions take place in the daily life of the most heartbreaking contexts and in spontaneous ways. The exhibition Tus manos están bien (Your hands are fine) is inspired by one of these moments.

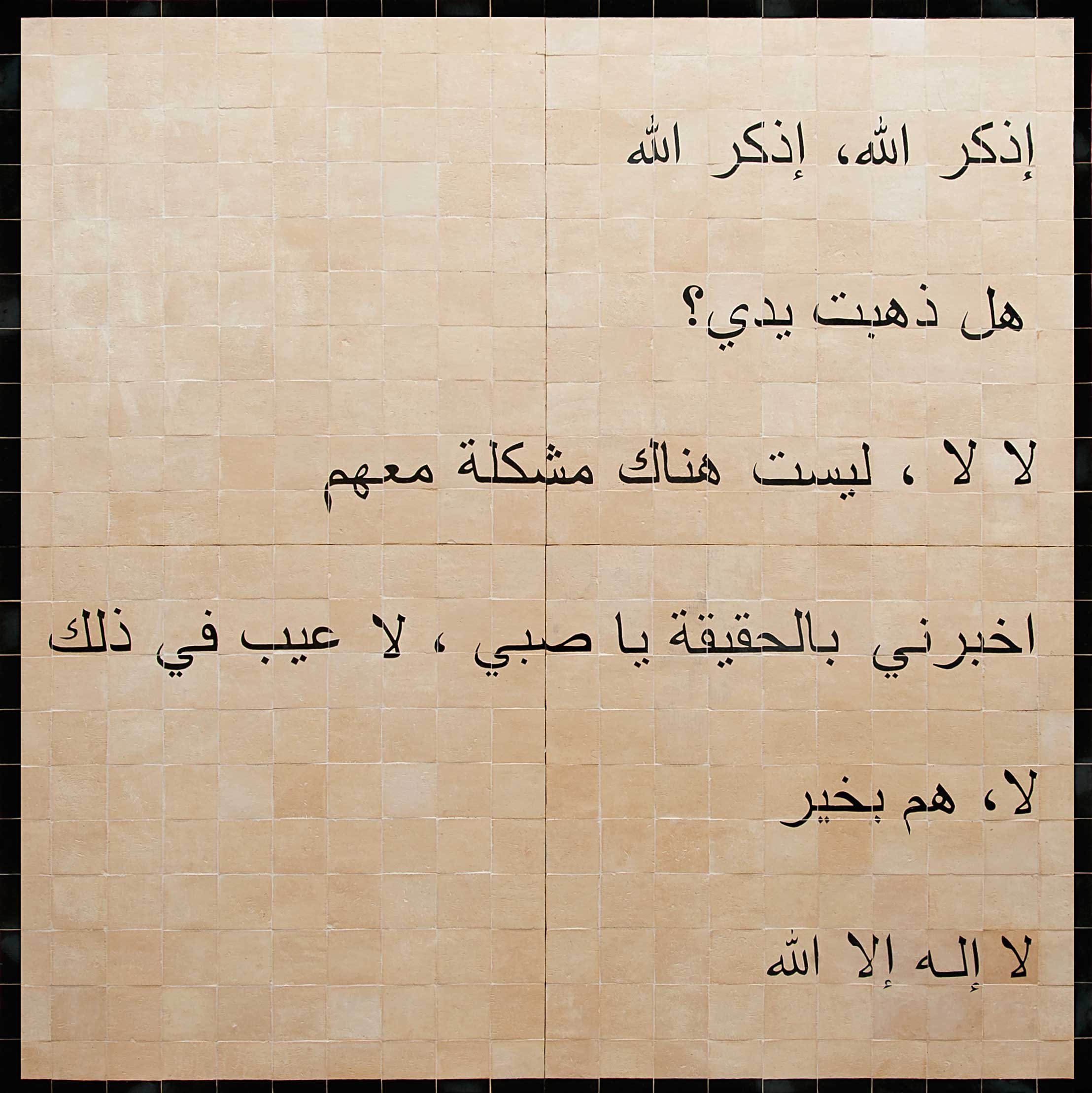

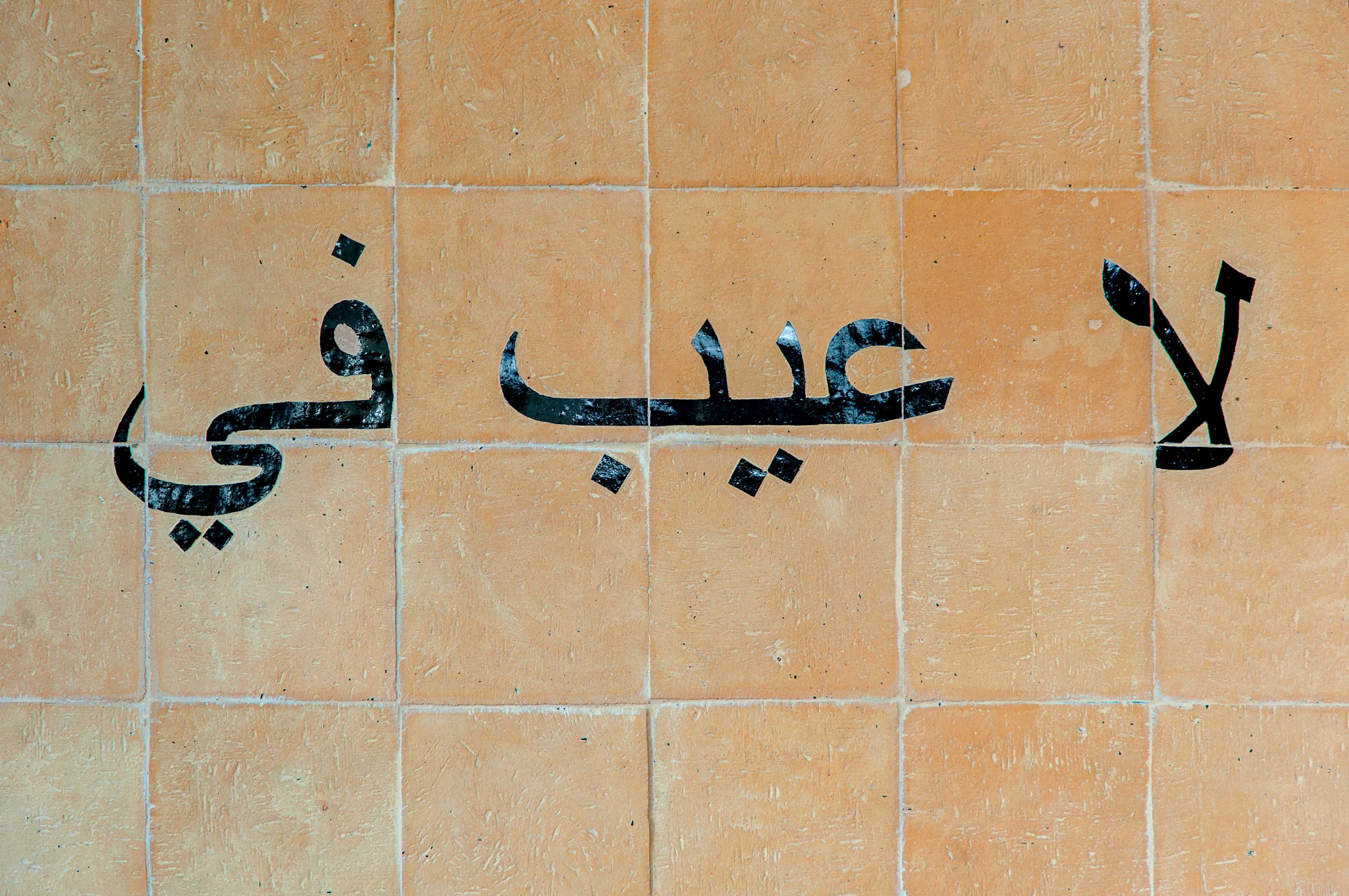

Dagoberto Rodríguez has successfully (de)coded a situation of almost mystical beauty that was recorded in a short video of rudimentary quality made by a combatant of the Syrian war and spread through the social network Twitter. After losing both his hands after firing an anti-tank missile on the outskirts of Damascus, an old man was comforted by his young battle partner. Against all evidence, he assured the injured soldier that his hands were fine and immediately invited him to praise God. The injured man agreed and said his prayer. It is an act of overwhelming and extreme faith. The dialogue, whose Psalmical structure resembles a Quranic verse, has been captured by Rodríguez in a mosaic mural made by hand using the ancient technique of Arabic tiling. Due to the opacity of the sign, which makes the Arabic characters unintelligible to the majority of the public in the West, the content of the conversation is hidden behind the beauty of calligraphy and its exquisite stone quality. The title of the piece, Tweet, synthesizes the contradictions between a hyperconnected world and the survival of premodern religious practices. On the other hand, the fact that the Syrian war is occurring in real time and by means of similar publications made by those same combatants and victims, has resulted in the reconfiguration of the role that conventional media has historically had in shaping the collective imagination and stories of armed conflicts. It involves, as it were, the rise of polyphonic stories that emerged from below, which complement, or even replace, the great narratives articulated by powerful television companies or the written press. In this way, this piece encompasses and exploits many of the multiple complexities that such a brief war scene may contain, such as that randomly found by the artist in the vastness of cyberspace.

Although formally Tweet seems to move away from Rodríguez´s previous work (which among other things has explored the intersections between design and art, and developed a very personal universe of watercolor images), his underlying concern powerfully and innovatively connects the piece with the previous trajectory of the artist. It is a work about faith, war, telecommunications and contemporary geopolitics, but, also, and above all, it is an inquiry into the power of the word. It is revealing that the aspect of the aforementioned video that has most attracted the attention of the artist was not the image itself, but, precisely, the dialogue, the beauty of the Arab characters and the fact that an oral exchange in a context of pain and urgency could be structured as poetry. This is not surprising if we consider that in Islam, language has a huge and comprehensive reach. It is one of the three religions commonly referred to as “from the book,” that is to say, they come from the belief that “the word” of God is contained in one or more texts that serve as the rules and spiritual guidance of its believers. It also has the peculiarity that its sacred book condenses two dimensions of language: writing and orality. Indeed, the word Quran is usually translated as “recitation” to underline the fact that the word of Allah is not limited to the written text, but must also be transmitted orally, through singing and recitation.

Rodríguez has demonstrated his intention to pay tribute to the man who lost his hands through this piece, whose refined quality is completely manual and requires enormous dedication and skill on the part of the craftsman. The image of “leaving your hands” modernizes the old counterpoint between weapons and words or, equally, war and art, two opposing forces that have remained alive in practically every culture on the planet throughout history. On a symbolic level, hands have great relevance in Arab culture: their use is regulated by sacred law and they are, together with the eyes, the most important aesthetic expression of the body. The hand is also the human tool par excellence. This has special value for an artist like Dagoberto Rodríguez, whose initial work within Los Carpinteros collective was focused on manual work with wood and other materials that are usually associated with crafts and not with fine art. Therefore, this return to the manual is a condemnation of that outdated hierarchy of creativity and a dialectical return within Rodríguez´s career. In general, and as we will see further on, the works that make up the exhibition are based on situations of complexity and contradiction (industrial and artisanal, technology and nature, high and low culture, art and war) that the artist synthesizes, resolves or comments on through humor and poetry.

It is important to highlight that the video that inspired the work was circulated on a social network, Twitter, whose concept and dynamic evoke the same mechanisms as oral communication (immediacy, replication and rapid circulation and gossip). By bringing the aforementioned dialogue to stone through an ancient artisan technique, a subtle contrast is established between the speed and volatility of the information disseminated through digital platforms and the old practice of capturing the texts in stone to make them last. Not least, in English the word twitter refers to the song of a bird, that is, it alludes to a natural order. However, at present and globally, this word is usually associated almost par excellence to the homonymous social network, that is, to the field of technology. This displacement of meaning makes evident the living and changing character of language, something that the school of analytical philosophy has underlined in the past. It was precisely one of the analytical philosophers, John L. Austin who, through theorizing about “speech acts,” concluded that things can literally be done with words. This means that language itself constitutes action and reality and is not limited to capturing them.

Language is and has been an element of great importance in the history and sensibility of Cuba. It could not be any other way in a country whose national hero is a poet. From the power of words, he knew how to satiate the Cuban revolution very well. Fidel Castro did not theorize about the act of speech and probably never even heard of John Austin. The philosopher, however, could well have used the Cuban leader as a reference in his dissertations on the performative power of language. Not without reason, analysts and historians have highlighted the importance that Castro gave to the dissemination and consolidation of his personal image in the mass media. Both locally and internationally, thousands of photos and videos managed to position him as a world icon, presenting him on many occasions as a charismatic and brave leader, and the Cuban revolution as a successful historical process of harmony and social justice. However, the propaganda of the regime was not transmitted exclusively through the exploitation of the technical image. Fidel Castro´s long speeches, as well as his lapidary and provocative phrases, have become a distinctive feature of his personality. The revolutionary rhetoric and its ideological slogans spread in the media and filled the streets of the island, whether they were written on the walls, displayed on fences or through posters in offices and schools. The Castro regime also knew how to appropriate the words of historical figures giving them new meanings at their convenience. The most paradigmatic case of this is probably that of the national hero José Martí, whose vocabulary in the struggle for independence in Cuba against Spain back in the 19th century was given anti-imperialist connotations towards the United States in accordance with the interests of the Cuban bloc-soviet during the cold war.

In the series Emblemas (Emblems) (2018) Rodríguez takes up some of these revolutionary slogans and presents them with the aesthetics of the American car logos of the mid-twentieth century. Those automotive vehicles, symbols of capitalist development in the United States after World War II, were disappearing from the streets of the world with the gradual incorporation of more recent models. It is a delightful paradox that in Cuba, these cars have remained in full use throughout sixty years of communism, even becoming part of the tourist-visual repertoire of Havana, where they are known as “almendrones”. In the Emblemas series, the logos of brands such as Ford, Pontiac and Cadillac have been replaced by phrases typical of Cuban political discourse and, sometimes, of popular speech. In this regard it is fascinating that, since revolutionary vocabulary and rhetoric are such suffocating presences in the lives of Cubans, some of the phrases of the revolution have been incorporated into colloquial speech after having passed through their respective processes of appropriation and deviation of meaning, almost always with a tendency towards humor and culture of the “jodedera” (banter). Again, language works in unpredictable ways. Finally, in this series, objects that once were brand identities and ostentation of luxury become carriers of radically different messages than they originally had, but also, and this is important, they become sumptuous objects thanks to the process of the commodification of art. In this way, the artist proposes an ironic wink towards the processes of circulation and fetishization not only of art, but also of discourses and ideologies.

The accelerated circulation of content and drifts of meaning have become increasingly common situations in this globalized world. For example, In 2006, journalist Spences Ackerman reported, the great success that the song Gasolina had among Kurdish fuel traffickers during the Iraq war. The strange and fascinating appropriation of one of the most representative tracks of reggaetón musician Daddy Yankee is a reliable example of the scope of this unusually successful music genre, which has been controversial because of the sexual content of some of its lyrics and the way it is danced to. And it is against rap and hip hop, two very similar music genres which reggaetón has been influenced by, the latter distinguishes itself due to being danceable music. Its most representative step is popularly known as “perreo”, and consists of shaking the hips with vigor and cadence. Its name refers to the fact that it is usually danced as a couple in a way that the arrangement of the bodies emulates the position that dogs and other animals use to perform intercourse. Nevertheless, and by virtue of the profuse media and social universe in which it emerged, reggaetón has developed very particular lyrics that, far from being constricted to sexual content, is full of references to regional and international politics and quotes from popular, mass and even so-called “high” culture from various regions of the planet. Attentively listening to some songs has revealed to Dagoberto Rodríguez some unexpected aspects of this type of music. He has focused on them to execute his recent Reguetón series.

The artist selected certain fragments of songs to inscribe them in stone. In this series, the fact that many reggaeton lyrics show little difference to political or religious discourses when they are removed from their original context is significant. On the other hand, on many occasions, and after its bustling vitalism and overwhelming aesthetics, there are underlying existentialist aspects that accuse the human search for the transcendence and meaning of life. The fact that the roots and impact of reggaeton are located especially in Puerto Rico and among Latino communities in the United States, has led to its contents being expressed equally through very local Spanish jargon as well as Spanglish. Despite the above, the genre has remained mainly in the Spanish-speaking realm, a situation that has caused unusual cultural twists worldwide, such as the fact that the most searched word on Google in 2017 was one spoken in Spanish (“despacito/slowly”, thanks to the song known by that same name popularized by Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee) or that the biggest stars in international music are looking to sing in Spanish and incorporate the reggaetón aesthetic more frequently in their productions with the intention of increasing their sales and popularity. Therefore, both musically and lyrically, reggaetón has produced texts with a dense cultural weight and has favored dynamics that underline and repower the multidirectional crossed identifications so characteristic of our time.

Despite the above, and as a result of the dynamic of the music industry, reggaeton has been classified and typecast simplistically as Latin music, and has remained in the international consciousness as such. An in-depth analysis such as that conducted by ethnomusicologist Wayne Marshall confirms the above, yet also highlights the transnational dimension of this cultural phenomenon, which is the result of exchanges and contamination between the cultural background of the circum-Caribbean region and American urban music. In reggaetón and its extensive stylistic circles, a productive pulse has also been established between the most recent technological resources and the presence of musical instruments and rhythmic patterns of ancestral Afro-Caribbean roots. In this context it is not surprising that the genre had an enormous impact on Cuba, but the Cubans, proud of the great musical contributions that their country has made to the world, have refused to speak of Cuban reggaetón and instead the term cubatón to refer to the local production of this type of music.

For a long time, and even today, the rejection of reggaeton was almost common place among the bulk of Latin American intellectuals and in certain social sectors in Spain. This has been mainly because of two reasons: a legitimate and attentive criticism of the sexist character of its lyrics, and the widespread belief that on a musical level it was a poor genre with few contributions. Regardless of whether both issues are widely discussed, it is certain that reggaetón is a complex and rich phenomenon that merits careful analysis. This was done in 2009 by a group of specialists whose academic and theoretical reflections were collected in a monographic volume published by Duke University in the United States. Ten years later, Puerto Rico´s political events have once again brought to light this cultural phenomenon, its impact on the configuration of subjectivities and its areas of contact/political impact. Following the leak of WhatsApp conversations between the now former governor of the island, Ricardo Rosselló, and eleven men from his nearby circle, Puerto Rican society, tired of decades of bad administrations, corruption and political class cynicism, took to the streets to demand the resignation of the governor. Among all the celebrities that supported the cause, singers Bad Bunny (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) and Residente (René Juan Pérez) particularly stood out. The song Afilando los cuchillos (Sharpening the knives), written and performed by the duet, became a kind of anthem for the protests, and social networks began to blaze with memes that compared the celebrities with ideologues and social-political leaders such as Karl Marx or Ernesto “Ché” Guevara.

Over twelve consecutive days dozens of rallies in repudiation of Roselló took place in Puerto Rico. On July 24, a massive dance/protest session gathered on the steps of the Metropolitan Cathedral of San Juan. A few hours prior to the event, singer-songwriter Tommy Torres posted on Twitter asking what time the event had been organized for. The tweet in question immediately went viral due to the accurate precision with which Torres referred to the collective dance session (“What time is that combative perreo on for?” were literally the musician´s words). The term “combative perreo” was coined to refer to this type of unusual practice of political, carnal, mass and festive opposition. The same night that the combative perreo took place, Ricardo Roselló resigned from his position.

In the works gathered here Dagoberto Rodríguez works with various textures and breaches of language. The shared setting of three apparently unrelated events in time, space and concept allows the artist to explore and reflect on the scope of language as a territory for the conformation of subjectivity, the configuration of stories and the exercise of power. The exhibition also includes different historical forms of writings and texts of a diverse nature. Your hands are fine serves as a kind of exhibition-book or, to be more precise, exhibition-tablet, establishing a historical-conceptual link with contemporary digital tablets and posing a collateral observation of history and the mechanisms of its elaboration. In these works, words matter and act. Rodríguez emphasizes the processes of a living story, which is written and erased, disseminated and made viral, sung and prayed. If, as Ludwig Wittgenstein said, the limits of our language are the limits of the world, in these exercises of enlargement, dislocation and linguistic diversions worlds widen and ideas shake (or perrean).

23/08/19

23/08/19

Diana Cuellar: Texto sobre exposición «Tus manos están bien», Ivorypress

Curator TextWords Matter

Lenguaje y geopolítica globalizada en la obra de Dagoberto Rodríguez

Globalized language and geopolitics in the work of Dagoberto Rodríguez

– Diana Cuéllar Ledesma

Un suceso perversamente bello tuvo lugar en mayo de 2016. Tras la toma de Palmira por parte de las tropas sirias, el gobierno ruso de Vladimir Putin organizó en las ruinas del anfiteatro romano de aquella ciudad un concierto sinfónico. Había pasado casi un año desde que el estado islámico realizara en ese mismo escenario, considerado por la Unesco patrimonio mundial de la humanidad, un video que registraba una suerte de performance escenificada (la autenticidad de la grabación nunca pudo comprobarse) en la cual un grupo de menores de edad asesinaba a veinticinco solados sirios delante de una multitud de espectadores sentados en la platea.

Bajo el lema “Oración por Palmira. La música revive las viejas murallas”, el concierto de la orquesta sinfónica del teatro Mariinsky de San Petersburgo en Palmira fue a todas luces una movida estratégica de Rusia para mejorar su imagen mediática tras su intervención en la guerra de Siria. No obstante, y al margen de las consideraciones geopolíticas, el portento estético del acontecimiento dio lugar a una imagen inusual de poesía en medio de la guerra. Sin embargo, aquel concierto fue un hecho preconcebido y cautelosamente orquestado. En contraste, muchos otros instantes de enorme dimensión estética tienen lugar en la cotidianidad de los contextos más desgarradores y de manera espontánea. La exposición Tus manos están bien se inspira en uno de ellos.

Dagoberto Rodríguez ha sabido (de)codificar una situación de belleza casi mística que fue consignada en un video de escasa duración y factura rudimentaria realizado por un combatiente de la guerra Siria y difundido a través de la red social Twitter. Tras perder ambas manos después de disparar un misil antitanques a las afueras de Damasco, un viejo recibía consuelo por parte de su joven compañero de batalla. Contra toda evidencia, este le aseguraba al herido que sus manos estaban bien y acto seguido lo invitaba a alabar a Dios. El herido le daba entonces la razón y después efectuaba sus plegarias. Se trata de un acto de fe sobrecogedor y extremo. El diálogo, cuya estructura salmódica recuerda a un verso coránico, ha sido capturado por Rodríguez en un mosaico mural realizado artesanalmente mediante la ancestral técnica de la azulejaría árabe. Gracias a la opacidad del signo, que hace a los caracteres árabes ininteligibles para la mayoría del público en occidente, el contenido de la conversación queda oculto tras la belleza de la caligrafía y su exquisita factura en piedra. El título de la pieza, Tweet, sintetiza las contradicciones entre un mundo hiperconectado y la pervivencia de prácticas religiosas premodernas. Por otra parte, el hecho de que la guerra de Siria esté siendo consignada en tiempo real y mediante aquel tipo de publicaciones realizadas por los mismos combatientes y víctimas, ha dado como resultado una reconfiguración del papel que los medios de comunicación convencionales han tenido históricamente en la conformación del imaginario y los relatos de los conflictos armados. Se trata, por así decirlo, de la emergencia de relatos polifónicos surgidos desde abajo, que complementan, o incluso sustituyen, a las grandes narrativas articuladas por poderosas compañías de televisión o la prensa escrita. De esta manera, la pieza contiene y explota muchas de las múltiples complejidades que puede llegar a contener una brevísima escena de guerra, como aquella encontrada aleatoriamente por el artista en la inmensidad del ciberespacio.

Aunque formalmente Tweet parece alejarse del trabajo previo de Rodríguez (quien entre otras cosas ha explorado las intersecciones entre diseño y arte, y desarrollado un muy personal universo de imágenes en acuarela) su inquietud de base conecta poderosa e innovadoramente la pieza con la trayectoria previa del artista. Es una obra sobre la fe, la guerra, las telecomunicaciones y la geopolítica contemporánea, pero, también, y sobre todo, es una indagación sobre el poder de la palabra. Resulta revelador que el aspecto del referido video que más haya llamado la atención del artista no fuera la imagen en sí, sino, precisamente, el diálogo, la belleza de los caracteres árabes y el hecho de que un intercambio oral en un contexto de dolor y urgencia fuese estructurado como poesía. Lo anterior no resulta extraño si consideramos que en el Islam el lenguaje tiene un enorme y abarcador alcance. Es una de las tres religiones comúnmente llamadas “del libro”, es decir, que parten de la creencia de que “la palabra” de Dios se halla contenida en uno o varios textos que fungen como reglamento y guía espiritual de sus creyentes. Tiene además la particularidad de que su libro sagrado condensa dos dimensiones del lenguaje: escritura y oralidad. En efecto, la palabra Corán suele ser traducida como «recitación» para subrayar el hecho de que la palabra de Alá no se limita al texto escrito, sino que debe también transmitirse de manera oral, mediante el canto y la recitación.

Rodríguez ha manifestado su intención de rendir homenaje al hombre que perdió sus manos mediante esta pieza cuya refinada factura es completamente manual y requiere enorme dedicación y destreza por parte del artífice. La imagen de “dejarse las manos” actualiza el viejo contrapunteo entre las armas y las letras o, lo que es lo mismo, la guerra y el arte, dos pulsiones contrapuestas que se han mantenido vivas en prácticamente todas las culturas del planeta a lo largo de la historia. A nivel simbólico, las manos tienen gran relevancia en la cultura árabe: su uso está regulado por la ley sagrada y son, junto con los ojos, la expresión estética corporal más importante. La mano es también la herramienta humana por excelencia. Esto tiene especial valor para un artista como Dagoberto Rodríguez, cuya obra inicial dentro del colectivo Los carpinteros estuvo focalizada en el trabajo manual con madera y otros materiales que suelen asociarse con la artesanía y no con el arte. Así, esta vuelta a lo manual es una condena a aquella trasnochada jerarquización de la creatividad y un retorno dialéctico dentro de la trayectoria de Rodríguez. En general, y según se irá viendo más adelante, las obras que componen la muestra parten de situaciones de complejidad y contradicción (industrial o artesanal, tecnología o naturaleza, alta o baja cultura, arte o guerra) que el artista sintetiza, resuelve o comenta con humor y poesía.

Es importante destacar que el vídeo que inspira la obra circulaba en una red social, Twitter, cuyo concepto y dinámica evocan los mecanismos propios de la comunicación oral (inmediatez, réplica y rápida circulación o cotilleo). Al llevar el mentado diálogo a la piedra mediante una antigua técnica artesanal, se establece un sutil contraste entre la velocidad y volatilidad de la información difundida mediante plataformas digitales y la vieja práctica de plasmar los textos en piedra para hacerlos perdurar. No menos importante, en inglés la palabra twitter refiere al canto de las aves, es decir, alude al orden de lo natural. Sin embargo, en la actualidad y a nivel global, dicha palabra suele asociarse casi por antonomasia a la red social homónima, o sea, al ámbito de la tecnología. Este desplazamiento de sentido hace evidente el carácter vivo y cambiante del lenguaje, algo que de antaño ha subrayado la escuela de la filosofía analítica. Fue precisamente uno de los filósofos analíticos, John L. Austin, quien, mediante su teorización sobre “los actos de habla”, llegó a la conclusión de que literalmente pueden hacerse cosas con palabras. Esto quiere decir que el lenguaje constituye en sí mismo acción y realidad y no solo se limita a capturarlas.

El lenguaje es y ha sido un elemento de suma importancia en la historia y sensibilidad de Cuba. No podría ser de otro modo en un país cuyo héroe nacional es un poeta. Del poder de las palabras supo abrevar muy bien la revolución cubana. Fidel Castro no teorizó sobre los actos de habla y probablemente ni siquiera oyó nunca hablar de John Austin. El filósofo, sin embargo, bien podría haber tomado al líder cubano como referente en sus disertaciones sobre el poder performativo del lenguaje. No sin razón, los analistas e historiadores han destacado la importancia que Castro dio a la difusión y consolidación de su imagen personal en los medios de comunicación masiva. Tanto a nivel local como internacional, miles de fotos y videos lograron posicionarlo como un ícono mundial, presentándolo en muchas ocasiones como líder carismático y valiente, y a la revolución cubana como un proceso histórico exitoso de concordia y justicia social. Sin embargo, la propaganda del régimen no pasó exclusivamente por la explotación de la imagen técnica. Los largos discursos de Fidel Castro, así como sus frases lapidarias y provocadoras, se han convertido ya en un rasgo distintivo de su personalidad. La retórica revolucionaria y sus consignas ideológicas se difundieron en los medios de comunicación y llenaron las calles de la isla, ya fuera escritas sobre los muros, desplegadas en vallas o a través de afiches en las oficinas y escuelas. El régimen castrista también supo apropiar palabras de personajes históricos dotándolas de nuevos sentidos según su conveniencia. El caso más paradigmático de este tipo de operación probablemente sea el del héroe nacional José Martí, cuyo vocabulario en la lucha de independencia de Cuba contra España allá en el siglo XIX fue provisto de connotaciones antiimperialistas hacia Estados Unidos de acuerdo con los intereses del bloque cubano-soviético durante la guerra fría.

En la serie Emblemas (2018) Rodríguez retoma algunas de aquellas consignas revolucionarias y las presenta desde la estética de los emblemas de los automóviles estadounidenses de mediados del siglo XX. Aquellos vehículos automotrices, símbolo del desarrollo capitalista de Estados Unidos tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, fueron desapareciendo de las calles del mundo con la paulatina incorporación de modelos más recientes. Es una deliciosa paradoja que en Cuba se hayan mantenido en pleno uso a lo largo de sesenta años de comunismo, llegando incluso a formar parte del repertorio turístico-visual de La Habana, en donde son conocidos como “almendrones”. En la serie Emblemas los logotipos de marcas como Ford, Pontiac y Cadillac han sido sustituidos por frases propias del discurso político cubano y, en ocasiones, del habla popular. Al respecto resulta fascinante que, al ser el vocabulario y la retórica revolucionarios presencias tan asfixiantes en la vida de los cubanos, algunas de sus frases hayan sido incorporadas al habla coloquial tras haber pasado por sus respectivos procesos de apropiación y desviación de sentidos, casi siempre con tendencia hacia el humor y la cultura de la “jodedera” (choteo). Nuevamente, el lenguaje trabaja de maneras imprevisibles. Finalmente, en la serie los objetos que otrora fueran identidad de marca y ostentación del lujo se convierten en portadores de mensajes radicalmente diferentes a los que en su origen tenían, pero también, y esto es importante, se reconvierten en objetos suntuarios merced a los procesos de mercantilización del arte. El artista establece así un guiño irónico hacia los procesos de circulación y fetichización no sólo del arte, sino también de los discursos y las ideologías.

La acelerada circulación de contenidos y las derivas de sentido se han convertido en situaciones cada vez más habituales en este mundo globalizado. En 2006 el periodista Spencer Ackerman reportó, por ejemplo, el gran éxito que la canción Gasolina tenía entre los traficantes de combustible de origen kurdo durante la guerra de Irak. Esa extraña y fascinante apropiación de uno de los temas más representativos del reguetonero Daddy Yankee es una muestra fehaciente de los alcances de este género musical inusitadamente exitoso, y que ha sido polémico por el contenido sexual de algunas de sus letras y la manera en que se baila. Y es que a diferencia del rap y el hip hop, dos géneros musicales muy cercanos y por los que el reguetón se ha visto influenciado, este último se distingue por ser música bailable. Su paso más representativo se conoce popularmente como “perreo”, y consiste en agitar las caderas con vigor y cadencia. Su apelativo refriere al hecho de que suele ser bailado en pareja de una manera tal que la disposición de los cuerpos emula la posición que los perros y otros animales emplean para realizar el coito. No obstante, y en virtud del profuso universo mediático y social en que ha surgido, el reguetón ha desarrollado una muy particular lírica que, lejos de constreñirse a los contenidos sexuales, está llena de referencias a la política regional e internacional y de citas de la cultura popular, de masas e incluso de la llamada “alta cultura” proveniente de diversas coordenadas del planeta. La escucha atenta de algunas canciones le ha descubierto a Dagoberto Rodríguez algunas facetas insospechadas de este tipo de música. En ellas se ha centrado para realizar su reciente serie Reguetón.

El artista ha seleccionado ciertos fragmentos de canciones para inscribirlos en piedra. En esta serie es significativo el hecho de que, extraídas de su contexto original, muchas letras de reguetón muestren escasa diferencia con el discurso político o el religioso. Por otra parte, en muchas ocasiones, y tras su bullicioso vitalismo y estética desbordante, subyacen aspectos existencialistas, que acusan la búsqueda humana por la trascendencia y el sentido de la vida. El hecho de que las raíces y el impacto del reguetón puedan localizarse especialmente en Puerto Rico y entre las comunidades latinas en Estados Unidos, ha llevado a que sus contenidos sean expresados lo mismo mediante jergas muy locales del español que en spanglish. Pese a lo anterior, el género se ha mantenido principalmente en el ámbito del habla hispana, situación que ha causado giros culturales insólitos a escala mundial, como el hecho de que la palabra más buscada en Google en el año 2017 haya sido una en castellano (“despacito”, merced a la canción homónima popularizada por Luis Fonsi y Daddy Yankee) o que las más grandes estrellas de la música internacional estén buscando cantar en español e incorporen con mayor frecuencia la estética reguetonera en sus producciones con la intención de aumentar sus ventas y popularidad. Así, tanto en lo musical como en lo lírico, el reguetón ha producido textos con una densa carga cultural y ha favorecido dinámicas que subrayan y repotencian la multivectorialidad de identificaciones cruzadas tan características de nuestro tiempo.

Pese a lo anterior, y como resultado de las dinámicas propias de la industria musical, el reguetón ha sido clasificado y encasillado de manera simplista como música latina y como tal se ha mantenido en los imaginarios internacionales. Un análisis profundo como el realizado por el etnomusicólogo Wayne Marshall confirma lo anterior, pero también destaca la dimensión transnacional de este fenómeno cultural, que no es sino el resultado de los intercambios y contaminaciones entre el bagaje cultural de la región circuncaribe y la música urbana estadounidense. En el reguetón y sus dilatados círculos estilísticos también se ha establecido un productivo pulso entre los recursos tecnológicos más recientes y la presencia de instrumentos musicales y patrones rítmicos de ancestral raigambre afrocaribeña. En este orden de cosas no resulta sorprendente que el género haya tenido enorme impacto en Cuba, pero los cubanos, orgullosos de los grandes aportes musicales de su país al mundo, se han negado a hablar de reguetón cubano y en cambio prefieren el término cubatón para referir a la producción local de este tipo de música.

Durante mucho tiempo, y aún hoy, el rechazo al reguetón fue casi un lugar común entre el grueso de la intelectualidad latinoamericana y en ciertos sectores sociales en España. Esto ha sido así principalmente a causa de dos razones: una legítima y atendible crítica al carácter sexista de sus letras, y la difundida creencia de que a nivel musical se trataba de un género pobre y de escasas aportaciones. Con independencia de que ambas cuestiones pueden ser ampliamente discutidas, lo cierto es que el reguetón es un fenómeno complejo y rico que amerita ser analizado cuidadosamente. Así lo hizo en 2009 un grupo de especialistas, cuyas reflexiones académicas y teóricas fueron recogidas en un volumen monográfico publicado por la universidad de Duke en Estados Unidos. Diez años más tarde, los sucesos políticos de Puerto Rico han vuelto a poner el foco en este fenómeno cultural, su impacto en la configuración de las subjetividades y sus zonas de contacto/impacto político. A raíz de la filtración de las conversaciones de WhatsApp entre el hoy ex gobernador de la isla, Ricardo Rosselló, y once hombres de su círculo cercano, la sociedad puertorriqueña, cansada de décadas de malas administraciones, corrupción y el cinismo de la clase política, salió a las calles para exigir la renuncia del gobernador. De entre todas las personalidades que apoyaron la causa, destacaron particularmente los cantantes Bad Bunny (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) y Residente (René Juan Pérez). La canción Afilando los cuchillos, escrita e interpretada por el dueto, se convirtió en una especie de himno para las protestas, y las redes sociales comenzaron a arder con memes que comparaban a aquellas celebridades con ideólogos y líderes político-sociales como Karl Marx o Ernesto “Ché” Guevara.

Durante doce días consecutivos decenas de concentraciones en repudio a Roselló tuvieron lugar en Puerto Rico. El 24 de julio se convocó a una sesión multitudinaria de baile/protesta en las escalinatas de la Catedral Metropolitana de San Juan. Unas horas antes de la cita, el cantautor Tommy Torres realizó una publicación en Twitter en la que preguntaba a qué hora había sido convocado el evento. El tuit en cuestión se viralizó de inmediato debido a la acertada precisión con la que Torres se refirió a la sesión de baile colectivo (“¿A qué hora es el perreo combativo ese?” fueron, literalmente las palabras del músico). Se acuñó así el término “perreo combativo” para referir a aquella insólita práctica de oposición política, carnal, multitudinaria y festiva. La misma noche en que el perreo combativo tuvo lugar, Ricardo Roselló renunció a su cargo.

En las obras aquí reunidas Dagoberto Rodríguez trabaja con diversas texturas y requiebros del lenguaje. La puesta en común de tres acontecimientos aparentemente inconexos en tiempo, espacio y concepto permite al artista explorar y reflexionar sobre los alcances del lenguaje en tanto que territorio para la conformación de la subjetividad, la configuración de los relatos y el ejercicio del poder. La exposición aglutina, además, diferentes formas históricas de escritura y textos de naturaleza diversa. Tus manos están bien se constituye así como una suerte de exposición-libro o, para ser más precisos, exposición-tabla, estableciendo un vínculo histórico-conceptual con las tabletas digitales contemporáneas y planteando una reflexión colateral sobre la historia y los mecanismos de su elaboración. En estas obras las palabras importan y hacen. Rodríguez enfatiza los procesos de una historia viva, que se escribe y se borra, se difunde y se viraliza, se canta y se reza. Si, como decía Ludwig Wittgenstein, los límites de nuestro lenguaje son los límites de nuestro mundo, en estos ejercicios de ampliación, dislocación y deriva lingüística los mundos se ensanchan y las ideas se agitan (o perrean).

16/08/19

16/08/19

Vesela Sretenović: LOS CARPINTEROS: A FINAL GOOD-BYE AT THE PHILLIPS

Curator Text

Los Carpinteros, the internationally acclaimed Cuban artist collective known for their immersive sculptural installations and large drawings, recently announced the dissolution of the group. After 26 years of collaboration—creating artworks that critique dominant ideologies and power structures with humor and political undertones—the two remaining members, Marco Castillo and Dagoberto Rodríguez, have decided to split and pursue separate artistic paths. I got to know them years ago when we started to discuss an Intersections contemporary art project for the Phillips. I love that their work beautifully blends playfulness of form and concept with a sense of subtle irony and intentional ambiguity, leaving openness for interpretation. I was fortunate to visit Marco in Havana this spring and Dago in Madrid just a couple of weeks ago before the news went public. We decided to move on with our project as planned and showcase it at the Phillips in fall 2019. Thereby, we reversed the museum’s tradition of celebrating “firsts” this time around to proudly be the last art institution to honor and say good-bye to this wonderful collective. Stay tuned for more information about the Phillips’s Los Carpinteros Intersections project.

Vesela Sretenović, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art